Friday, March 23, 2012

Ball of Twine Open Forum

FOA: "They will not be pushing on a string; rather picking up the ball of twine and throwing it!"

I may be crazy, but if there was a contingency plan/how-to manual on throwing the world's largest ball of twine, it might just look like this:

And here are a few twine throwing excerpts from our brain-trust of central planners:

By the authority vested in me as President by the Constitution and the laws of the United States of America, including the Defense Production Act of 1950 [...] it is hereby ordered as follows:

...

Sec. 103. General Functions. Executive departments and agencies (agencies) responsible for plans and programs relating to national defense (as defined in section 801(j) of this order), or for resources and services needed to support such plans and programs, shall:

(a) identify requirements for the full spectrum of emergencies, including essential military AND civilian demand;

(b) assess on an ongoing basis the capability of the domestic industrial and technological base to satisfy requirements in peacetime AND times of national emergency, specifically evaluating the availability of the most critical resource and production sources, including subcontractors and suppliers, materials, skilled labor, and professional and technical personnel;

...

Sec. 201. Priorities and Allocations Authorities. (a) The authority of the President conferred by section 101 of the Act, 50 U.S.C. App. 2071, to require acceptance and priority performance of contracts or orders (other than contracts of employment) to promote the national defense over performance of any other contracts or orders, and to allocate materials, services, and facilities as deemed necessary...

(b) The Secretary of each agency delegated authority under subsection (a) of this section (resource departments) shall plan for and issue regulations to prioritize and allocate resources and establish standards and procedures by which the authority shall be used to promote the national defense, under both emergency AND non-emergency conditions.

...

PART III - EXPANSION OF PRODUCTIVE CAPACITY AND SUPPLY

Sec. 301. Loan Guarantees. (a) To reduce current or projected shortfalls of resources, critical technology items, or materials essential for the national defense, the head of each agency engaged in procurement for the national defense, as defined in section 801(h) of this order, is authorized pursuant to section 301 of the Act, 50 U.S.C. App. 2091, to guarantee loans by private institutions.

(b) Each guaranteeing agency is designated and authorized to: (1) act as fiscal agent in the making of its own guarantee contracts and in otherwise carrying out the purposes of section 301 of the Act; and (2) contract with any Federal Reserve Bank to assist the agency in serving as fiscal agent.

...

Sec. 302. Loans. To reduce current or projected shortfalls of resources, critical technology items, or materials essential for the national defense, the head of each agency engaged in procurement for the national defense is delegated the authority of the President under section 302 of the Act, 50 U.S.C. App. 2092, to make loans thereunder. Terms and conditions of loans under this authority shall be determined in consultation with the Secretary of the Treasury and the Director of OMB.

...

Sec. 303. Additional Authorities. (a) To create, maintain, protect, expand, or restore domestic industrial base capabilities essential for the national defense, the head of each agency engaged in procurement for the national defense is delegated the authority of the President [...] to make provision for purchases of, or commitments to purchase, an industrial resource or a critical technology item for Government use or resale, and to make provision for the development of production capabilities, and for the increased use of emerging technologies in security program applications, and to enable rapid transition of emerging technologies.

...

Sec. 304. Subsidy Payments. To ensure the supply of raw or nonprocessed materials from high cost sources, or to ensure maximum production or supply in any area at stable prices of any materials in light of a temporary increase in transportation cost, the head of each agency engaged in procurement for the national defense is delegated the authority of the President [...] to make subsidy payments, after consultation with the Secretary of the Treasury and the Director of OMB.

...

Sec. 306. Strategic and Critical Materials. The Secretary of Defense, and the Secretary of the Interior in consultation with the Secretary of Defense as the National Defense Stockpile Manager, are each delegated the authority of the President [...] to encourage the exploration, development, and mining of strategic and critical materials and other materials.

...

Sec. 308. Government-Owned Equipment. The head of each agency engaged in procurement for the national defense is delegated the authority of the President [...] to:

(a) procure and install additional equipment, facilities, processes, or improvements to plants, factories, and other industrial facilities owned by the Federal Government AND to procure and install Government owned equipment in plants, factories, or other industrial facilities owned by private persons;

(b) provide for the modification or expansion of privately owned facilities, including the modification or improvement of production processes...

(c) sell or otherwise transfer equipment owned by the Federal Government and installed under section 303(e) of the Act, 50 U.S.C. App. 2093(e), to the owners of such plants, factories, or other industrial facilities.

...

Sec. 310. Critical Items. The head of each agency engaged in procurement for the national defense is delegated the authority [...] to take appropriate action to ensure that critical components, critical technology items, essential materials, and industrial resources are available from reliable sources when needed to meet defense requirements during peacetime, graduated mobilization, and national emergency. Appropriate action may include restricting contract solicitations to reliable sources, restricting contract solicitations to domestic sources (pursuant to statutory authority), stockpiling critical components, and developing substitutes for critical components or critical technology items.

...

Sec. 312. Modernization of Equipment. The head of each agency engaged in procurement for the national defense [...] may utilize the authority of title III of the Act to guarantee the purchase or lease of advance manufacturing equipment, and any related services with respect to any such equipment for purposes of the Act. In considering title III projects, the head of each agency engaged in procurement for the national defense shall provide a strong preference for proposals submitted by a small business supplier or subcontractor...

You can read the full 11-page Executive Order here.

Sincerely,

FOFOA

Great comment, Jeff!...

You guys don't have to worry about being pressganged into being unpaid 'consultants'. Those jobs will go to Buffett, Jeff Immelt, etc. who want to help the G out of the goodness of their hearts...and to protect their position near the fiat firehose of course.

Honestly, the fascist talk gets in the way of understanding what is going on. Yes, this is the Declaration of Hyperinflation, but did you expect the G to just sit on its hands and collapse?

FOFOA: "In parts two and three of my September hyperinflation posts I explained how the US government MUST respond to a currency collapse by printing more currency in order to keep its stooges doing its bidding...

Gonzalo correctly points to "palliative printing" as a wheelbarrow-enlarging event, which comes at the very end stage of a hyperinflation. And he presents it as palliative to the people. But this printing is usually most palliative to the government and its expanding rank of stooges. Sure, there will be "welfare" along the way, but for the most part the freshly printed cash will buy the most goods and services for the first hands it touches. And then less for the second. And even less for the third and so on. And this prime purchasing power will be mostly reserved for the government that prints it."

This EO, IMO, means that the hour is getting late...

Friday, March 16, 2012

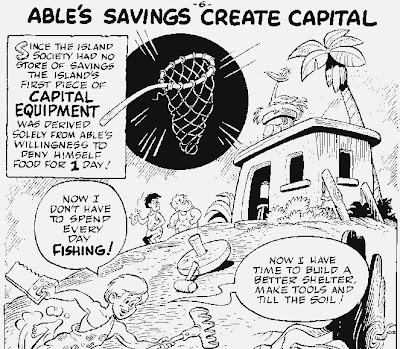

Sushi Island Savers Saga - Part 2

Great comments in the last thread! I wrote the following as a comment replying to a few questions that had come up relating to how the act of saving or net production contributes to the Superorganism's drive toward sustainable growth. But I really wanted as many people as possible to watch the video below, so I thought it would be more prominent in a post. So here you go!

The term "Superorganism" refers first and foremost to "distributed intelligence" or "market intelligence" as opposed to "centralized planning". If ever you feel the urge to make life better by changing some rule or adding a new one in order to control, cause or stop someone else's actions, you fall under the category of central planners. If, however, you are driven to personal actions to better your life (rather than the all too common obsession with changing the actions of others you deem to be wrong) you are part of the Superorganism. Central planners are, of course, also part of the Superoganism, but they are a retarding influence on that which would be far more intelligent without them.

Both distributed intelligence and central planning are capable of organizing the means of production. It's just that one does it infinitely better than the other so there's really no comparison. Somewhere along the way, probably in the 20s and 30s, governments switched from assisting the Superorganism to central planning, or retarding the Superorganism. I believe the singular factor that enabled this switch—made it even possible—was that the savers began entrusting their surplus production to the government as a fundamental function of changes to the monetary system that occurred in 1922.

Not everyone is capable of being a world-changing entrepreneur. But everyone is capable of consuming less than they produce and, therefore, saving. And it is the choices made by billions of average people that leads to the Superorganism's superior intelligence. As the video below explains, markets are processes of learning and mutual discovery through individual choices like entrepreneurship (individuals taking a creative stab at the future in the face of uncertainty) and the spread of knowledge (individuals building upon—expanding upon—the past contributions of others).

The chain of settlement amongst savers which I described in this comment is like a battery system for the storage of economic power. It gains its power and its storage ability from its perpetual nature. Economic power can be deployed or discharged at any time by any saver because there are always new net producers working to join the chain. Without this system of reserves, the surplus production of savers simply gets distributed and used up by whatever activity the debtors are up to at that time, or wherever the central planners want to allocate it. With the Freegold system, the allocation of stored purchasing power becomes a matter of the individual decisions of billions of savers with no reason to hurry.

I do realize that most scholarly Austrian economists probably ignore this blog because it seems somehow not up to their standards. Likewise, my readers tend to look down on modern Austrians because they are, for the most part, "Hard Money Socialists" as Ari and FOA dubbed them more than a decade ago. The Socialist part is because, even while they talk about limited government, they want the government to control the production of money "by locking gold into any official currency system to act as a gauge and controlling factor against socialist tendencies in government" (to quote FOA). Socialism is about non-market prices and any official gold standard is a Socialist standard.

But I want to caution you against dismissing the Austrian School simply because most modern practitioners are misguided with respect to their monetary prescriptions. The Austrian School is primarily a school of Economics (focused on subjectivism and a deductive approach to economics called praxeology), not money, and this is where it is truly great. From my limited time spent in the Austrian space, I am probably most impressed with Israel Kirzner among the living Austrians. His focus is more on the period of Austrian Economics before 1974 than it is on the activities of modern practitioners.

And I think you'll find that this video below, a lecture given by Kirzner this past summer, is so spot-on with regard to the discussion in the last thread that I want to say it is a must-watch for anyone following the discussion. Even if you've seen it before, or the older, longer and more complete version, you may want to watch it again:

And just for fun, here's the story of an intelligent super-sized organism named Nellie who finally had enough of the circus telling her what to do:

Sunday, March 11, 2012

Savings & Capital Theory Open Forum

The monetary plane is only relevant insofar as it directs and facilitates the flow of the physical plane. Part of what pisses people off so much about the $IMFS is that it seems to direct and facilitate the flow of massive amounts of cool physical plane stuff into the hands of those who contribute little more than tweaking the monetary plane in their favor. But we must remember that they are not producing the stuff that they are enjoying. They are simply receiving it.

It is the physical plane that drives the flow. It is the producers that produce the stuff. And it is the net-producers that produce enough extra stuff that it can accumulate in the possession of the monetary plane managers. It is the savers that drive the economy. Savers are net-producers. Net-producers are savers.

I have another big idea post that I'm working on, but I'm finding it difficult to make progress because the stunning revelation I am trying to share with you rests on so many complicated foundations. Without giving too much away, I guess I could say it will be a continuation of some of the themes introduced in Moneyness. So I had this idea that I could dispense with some of my difficulty by just putting a little bit here in an open forum.

Recall the story of "I, Pencil" from the Superorganism Open Forum. The Austrian's taught us that "capital" is not merely a lump of some homogeneous substance. It is a complex structure of various goods used in specific combinations to produce other goods. Capital, in essence, is a product of the Superorganism. All else is simply unsustainable malinvestment. How long managed malinvestment can continue before the whole superstructure collapses seems to be the only real question.

Rather than getting into who should be making the decisions that lead to capital formation and economic growth in the physical plane, I'm more interested in how relevant the $IMFS is to that process at this point. Does the $IMFS transmit any price information that is relevant to the Superorganism anymore? The Superorganism is a robust creature. It can work around a badly mismanaged superstructure and still produce marvelous creations. But there comes a point when the signals transmitted by the system become so detrimental to the Superorganism's natural drive toward sustainability that it must be abandoned for good.

One of the flaws of the $IMFS is that it does view "capital" as a homogeneous lump. And because it is a monetary system managed by net-consumers, it attempts to redirect all capital to the consumption end of the spectrum, where it (the $IMFS) feeds. When you first start this process of capital consumption, everything is really nice. Imagine that you decided to quit work tomorrow and start liquidating your gold to your heart's content. You could live high on the hog for a while! This is the $IMFS. But if you think it through for a minute, you'll realize that the better life is each day, the sooner you'll run out of gold.

Savers drive the economy, and the $IMFS consumes it. And what of investment? The $IMFS heaps the greatest rewards on those who invest in consumables, like APPL, rather than infrastructure or higher order capital goods. The concepts I hope you'll think about and discuss in the comments are the physical plane versus the monetary plane, savings and capital. The physical plane is all that matters. The monetary plane only exists to assist the Superorganism by transmitting information through prices and lubricating the flow. Savers drive everything. If they are saving, the economy will expand (sustainably or unsustainably). If they are not saving, the economy will contract. The Superorganism's natural drive is toward economic sustainability while the $IMFS is a pedal-to-the-metal consumption binge thrill ride toward economic collapse.

Below is an excerpt from Freegold Foundations discussing capital and savings. Sorry about the length of the excerpt, but if you don't like long posts, you're probably at the wrong blog. After that I'll end this post with a neat little island analogy on the topic of capital consumption, or how to kill an economy in style. Everybody loves island analogies, right?

Freegold Foundations

Capital

I'm not going to go into great detail on the concept of capital, other than to give you a mental exercise. Because the term "capital" can be quite confusing in our modern paper/electronic world, I want you to imagine a much simpler human civilization. Imagine an ancient Greek city. All the buildings made of stone and mud, the horse carts and agricultural tools, the linens and skins worn as clothing, the knowledge base passed down through generations; all these creations of man's intellect were the capital of the time.

Now imagine the destruction of capital. Imagine an earthquake or volcano that destroys the fruits of many generations. Or a plague or war, perhaps, that destroys the knowledge base. That's the loss of real wealth you are imagining. And it is this cycle of capital creation and destruction that tells the story of mankind throughout many civilizations.

In modern economics, the word "capital" accounts for many specific things. But I think it is helpful to consider this word in a more basic, fundamental way. Think of it in terms of capital creation, capital employment and capital consumption or destruction. Modern economics would not call consumables capital, which is why I am suggesting a different approach to the word. When we are productive, imagine we are creating this thing called capital. We may figure out a way to turn someone else's capital, combined with our own prowess, into more capital. This would be the employment of capital. And sometimes we simply consume it, or use it up.

If I build a house I have created capital. By owning and living in a home, I am consuming that capital slowly. If I were to buy a specialized tool and use it to make something new, then I have employed capital to create more capital. Is this view of "capital" clear, or woolly?

Savings

Savings are the result of one's production being greater than his consumption. Saving is the convention for deferring the fruits of capital creation—earned consumption—until later. Savings is also the way we hand off capital to the next person who will use it to create more capital. And when it is done right, saving results in the accumulation of capital throughout society at large. When it is done poorly, saving results in the aggregate destruction of capital through frivolous consumption and mal(bad)investment (the misguided employment of capital) resulting in unsustainable infrastructures built on unstable levered foundations.

Here's where it may get a bit counterintuitive. You might, if you were Charlie Munger, think that the best way to pass your earned capital on to another producer is through paper. If you save in paper notes then you are loaning your earned capital to the next producer in line, right? And if you buy gold Charlie says you're a jerk, even if it works, because he thinks you are pulling capital out of the system. But are you really? I bring this up (and please watch a minute or so of that video starting at 1:04:05) because it is the key to this discussion about savings.

We should think about the global economy in terms of production and consumption in the physical realm as opposed to the financial or monetary realm, what I like to call the physical plane versus the monetary plane. A "net producer" produces more capital than he consumes. Likewise, a "net consumer" consumes more than he produces. The global aggregate is generally net-neutral on this production-consumption continuum. I say "generally" because there are times of expansion and times of contraction, so taking time into account, we are "generally" net-neutral (or close to it) as a planet. At least that's the way it is under the global dollar reserve standard.

On the national scale, however, we are all both blessed and cursed by the presence of government. Governments are always net consumers, as it is their very job to redistribute part of our private savings into the infrastructure and secure environment that enables us to produce capital in the way that we do. Government's job is not to produce capital, but to enable and support the private production (and accumulation) of capital!

Being such that human society has evolved in this way, we private citizens must, in aggregate, be net producers so that government can net consume. And we become net producers by saving. Therefore we enable and support our own future net productivity by saving some of our past production of capital today, in the form of savings.

The financial system is really just the monetary plane's record-keeper of this vital process that actually takes place on the physical plane. In its modern incarnation, the global financial system has allowed for a strange international balancing act whereby (literally) one whole side of the planet's net production has allowed the other side to net-consume for decades on end. But this is an unsustainable anomaly, and it is beside the point of this discussion. So please push this giant, global imbalance-elephant in the room over to the corner while we continue this discussion about savings.

The question we must answer here is: Is Charlie Munger right? Are you a good person only if you put your savings into paper where it can be easily redistributed, and a jerk if you buy gold, depriving the paper whores of your savings? Is this the way it works in reality? Or is this simply the sales pitch of one with great bets riding on the continued popularity of paper savings?

The government confiscates a portion of the physical capital created in the private sector through several means. Taxation is one way, forcing you to keep a portion of your earnings in paper so that it can be easily transferred to the government and then used to buy up capital from the marketplace. This forces you to leave some of your production in the marketplace to be taken by the government, preventing you from consuming an amount equal to your productive output.

Printing money, or its modern equivalent, quantitative easing, is another way the government can confiscate real capital from the marketplace without first producing a commensurate amount. This method inflicts what we call "the inflation tax." The "victims" of this confiscation are anyone and everyone holding (and saving) the currency or any paper asset fixed to it, and the damages are relative to the amount of currency each "victim" is holding. Because this form of confiscation is spread so wide and thin, it is mostly not even noticed by the private sector.

The last way the government confiscates capital is by borrowing it directly from the net producers in the private sector. When you buy US bonds, it is you that are loaning your earned claims on capital to the government. So we can see that the government has plenty of ways to create its own claims on capital in the marketplace without first producing a commensurate market contribution (because governments are always net consumers).

In fact, the modern financial system has bestowed these same powers, creating market claims without contribution, upon the private sector as well. I'm not talking about private banks loaning money into existence, for this process has no market contribution from which to feed. It is directly price inflationary until the debtor makes a market contribution to work it off.

What I'm talking about is the private sector's ability to sell unlimited amounts of this debt to the savers, funding the marketplace claims to consumers/debtors with real marketplace capital (contributed by the savers). Private banks that would normally be constrained by their balance sheets for their own survival can now offload that constraint onto the net producers, making themselves—the banks—totally unconstrained.

The banking system sells all kinds of packaged debt to net producers, the savers. It creates this stuff at will to meet demand. And if necessary, it drums up new debtors one way or another to keep this stuff financially funded. Even corporations can dilute their paper shares to take in new claims from the savers without giving up a commensurate marketplace contribution.

This is the process of paper savings hyperinflation. It is a self-feeding, self-fulfilling, self-sustaining, self-propelling system that will ultimately lead to real price hyperinflation. When you produce capital and decide to leave it in the marketplace, postponing your earned consumption until later, and you do so in any paper investment, you are feeding this process of capital destruction through paper savings hyperinflation.

If you buy government debt you are feeding, enabling the growth of government beyond its most basic mandate, providing the infrastructure and secure environment that enables us to produce capital. And if you think an expanding government is good, just beware that all governments are stupid!

"The institution of government was invented to escape the burden of being smart. Its fundamental purpose is to take money by force to evade the market's guidance to have the privilege of being stupid." Richard Maybury goes on (in the linked video) to say that private organizations that petition government for special protections, subsidies and incentives are asking for the same privilege. They want to be relieved of the burden of being smart.

(Not since the Agriculture Adjustment Act of 1933 that paid farmers to destroy crops during the Great Depression in an attempt to raise the price of crops, has there been a more obvious example of government's propensity for destroying real world capital than the 2009 "Cash for Clunkers" program, whereby government literally paid private car dealerships to pour sugar into running car engines ensuring their permanent destruction.)

This is why, when you save in government paper, you are enabling malinvestment and the destruction of capital that goes along with it. And it's the destruction of the capital that you just contributed to the marketplace that you are feeding. The same goes for the private sector. When you save in private paper you are enabling the expansion of frivolous consumption (beyond natural market constraint) and the destruction of your capital contribution to the marketplace that goes along with it.

So what's the alternative? If both public and private paper savings contribute to the expansion of malinvestment, net-consumption and systemic capital destruction, what is a net producer to do? If one wants to produce more capital than he consumes—for the good of the economy—yet he doesn't want to work for free, what is he to do? Or if one wants to produce more than she consumes—for the good of her retirement years and her family's future—what is she to do?

The monetary plane, the modern dollar-based global financial system, has failed these individuals. So what is left? The physical plane? If these individuals trade their earned marketplace credits in for physical capital without employing that capital in productive enterprise, then they are either consuming that capital (capital destruction) or denying other producers the use of it (hoarding, also destructive to the capital creation process). This is not only detrimental to society at large, but also to the future value of your savings that depends on new capital being plentiful in the marketplace when you deploy your savings in the future.

But of course there is one item, one physical asset, that stands out above all the rest. And this isn't some new discovery by FOFOA. Man discovered that this was gold's highest and best use thousands of years ago. Once you've produced capital for the marketplace, whatever asset class you choose to deploy your earned credits into will feel the economic pressure to rise in price. If the monetary plane was volume-fixed (or even constrained), it too would rise in price as real capital is added to the economy. But it has become a system that expands in volume rather than rising in price.

This is hyperinflation: quantitative expansion of savings! If the pool of savings rose only in value and not quantity, then each new net producer would have to bid "savings" away from an old net producer, and "savings" would retain their proper relationship to the pool of real marketplace capital available for purchase.

If you choose to deploy your credits into the everyday physical plane, the tangible goods plane, prices will rise. If all the savers chose oil for example, we'd all pay very high prices at the gas pump. Or choose agriculture for your savings and we'll all have to work an extra hour to feed ourselves. No, you want to choose something that both rises in price (rather than expanding in volume) and also something that does not infringe on others or economically impede the capital creation process that feeds value to your savings. And as an added bonus, if everyone chooses the same thing, it works extra well. This is called the focal point.

But for gold to fulfill this vital function in the capital creation process, it needs to trade in a fixed (or at least constrained) quantity that will allow its price to rise every time a new capital net-increase is contributed to the marketplace. And, unfortunately, paper gold and fractional reserve bullion banking doesn't allow this process to work properly. In fact, it makes paper appear generally competitive, even to gold.

So what about Charlie Munger? Is he right? Are you a jerk if you buy gold? Well, yes and no. If he's talking about paper gold, then yes! But likewise, it seems you are a jerk if you buy Charlie's paper as well! And you're an even bigger jerk if you buy physical commodities and tangible goods without the intention of employing them in real economic activity. It seems—and correct me if I'm wrong here—that physical gold (along with a few other discreet collectible items like real estate, fine art, antique furniture, ancient artifacts, fine gemstones, fine jewelry and rare classic cars) may be the only true wealth holdings in which you are not a jerk. What do you think?

________________________________________________________

And finally, here is a fun little excerpt from Robert P. Murphy's 2008 article, The Importance of Capital Theory:

A Sushi Model of Capital Consumption

Above I've pointed out some of the basic flaws in Krugman's and Cowen's arguments. (Other Austrians have responded to Krugman in the past. See the replies of Garrison and Cochran.) More generally, they are ignoring the all-important notion of capital consumption. This is why one needs to understand capital theory, as pioneered by Carl Menger and Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, in order to make sense of what the heck just happened in the US economy. Any talking head on CNBC who doesn't understand capital consumption is going to give horrible policy recommendations.

When thinking about this article, I went back and forth. I have decided that I should spell out a "model" of intermediate complexity, because if I simplify it too much, it might not really click with the reader, but if I go overboard with it, no one in his right mind would finish the article. Without further ado, let's examine a hypothetical island economy composed of 100 people, where the only consumption good is rolls of sushi.

The island starts in an initial equilibrium that is indefinitely sustainable. Every day, 25 people row boats out into the water and use nets to catch fish. Another 25 of the islanders go into the paddies to gather rice. Yet another 25 people take rice and fish (collected during the previous day, of course) and make tantalizing sushi rolls. Finally, the remaining 25 of the islanders devote their days to upkeep of the boats and nets. In this way, every day there are a total of (let us say) 500 sushi rolls produced, allowing each islander to eat 5 sushi rolls per day, day in and day out. Not a bad life, really, especially when you consider the ocean view and the absence of Jim Cramer.

But alas, one day Paul Krugman washes onto the beach. After being revived, he surveys the humble economy and starts advising the islanders on how to raise their standard of living to American levels. He shows them the outboard motor (still full of gas) from his shipwreck, and they are intrigued. Being untrained in economics, they find his arguments irresistible and agree to follow his recommendations.

Therefore, the original, sustainable deployment of island workers is altered. Under Krugman's plan for prosperity, 30 islanders take the boats (one with a motor) and nets out to catch fish. Another 30 gather rice from the paddies. A third 30 use the fish and rice to make sushi rolls. In a new twist, 5 of the islanders scour the island for materials necessary to maintain the motor; after all, every day it burns gasoline, and its oil gets dirtier. But of course, all of this only leaves 5 islanders remaining to maintain the boats and nets, which they continue to do every day. (If the reader is curious, Krugman doesn't work in sushi production. He spends his days in a hammock, penning essays that blame the islanders' poverty on the stinginess of the coconut trees.)

For a few months, the islanders are convinced that the pale-faced Nobel laureate is a genius. Every day, 606 sushi rolls are produced, meaning that everyone (including Krugman) gets to eat 6 rolls per day, instead of the 5 rolls per day to which they had been accustomed. The islanders believe this increase is due to use of the motor, but really it's mostly due to the rearrangement of tasks. Before, only 25 people were devoted to fishing, rice collection, and sushi preparation. But now, 30 people are devoted to each of these areas. So even without the motor, total daily output of sushi would have increased by 20%, assuming the islanders were equally good at the various jobs, and that there were plenty of fish and rice provided by nature. (In fact, the contribution of the motor was really only the extra 6 rolls necessary to feed Krugman.)

But alas, eventually the reduction in boat and net maintenance begins to affect output. With only 5 islanders devoted to this task, instead of the original 25, something has to give. The nets become more and more frayed over time, and the boats develop small leaks. This means that the 30 fishermen don't return each day with as many fish, because their equipment isn't as good as it used to be. The 30 islanders making sushi are then in a fix, because they now have an imbalance between rice and fish. They start cheating, by putting in smaller pieces of fish into each roll. The islanders continue to get 6 rolls per day, but now each roll has less fish in it. The islanders are furious — except for those who are repulsed by the idea of ingesting raw fish.

Being a trained economist, Krugman knows what to do. He suggests that 2 of the rice workers and 2 of the sushi rollers switch over to help the fishermen. Now with 34 workers, the islanders are able to catch almost as many fish per day as they were in the previous months, even though they are now using tattered nets and dilapidated boats. Krugman — being very sharp with numbers — moved just enough workers so that the fish caught by the 34 islanders matches up perfectly with the rice picked by the remaining 28 islanders who go to the paddies every day. With this amount of fish and rice, the 28 workers in the rolling occupation are able to produce 556 sushi rolls per day. This allows everyone to consume about 5 and a half rolls per day, with a bonus roll left over for Krugman.

The islanders are a bit concerned. When they first followed Krugman's advice, their consumption jumped from 5 rolls to 6 per day. Then when things seemed to be all screwed up, Krugman managed to fix the worst of the discoordination, but still, consumption fell to 5.5 rolls per day. Krugman reminded them that 5.5 was better than 5. He finally got the crowd to disperse by talking about "Cobb-Douglas production functions" and drawing IS-LM curves in the sand.

Because this is a family-friendly website, we will stop our story here. Needless to say, at some point the 5 islanders devoted to net and boat production will decide that they have to cut their losses. Rather than trying to maintain the original fleet of boats and original collection of nets with only 5 workers instead of 25, they will instead focus their efforts on the best 20% of the boats and nets, and keep them in great shape. At that point, it will be physically impossible for the islanders to prop up their daily sushi output. In order just to return to their original, sustainable level of 5 sushi rolls per person per day, the islanders will need to suffer a period of privation where many of them are devoted to net and boat production. (We can only hope that Professor Krugman has been rescued by the Swedes by this time.)

The 5 people looking for ways to synthesize gasoline and motor oil will have to abandon that task, because it was never appropriate for the islanders' primitive capital structure. The islanders will of course discard the motor brought to the island by Krugman once it runs out of gas.

Finally, we predict that during the period of transition, some islanders will have nothing to do. After all, there will already be the maximum needed for catching fish with the usable boats and nets, and there will already be the corresponding number of islanders devoted to rice collection and sushi rolling, given the small daily catch of fish. There would be no point in adding extra islanders to boat and net production, because then they would end up building more than could be sustained in the long run. Hence, the elders rotate 10 people every day, who are allowed to goof off. They could of course go try to catch fish with their bare hands, or go gather rice that would just be eaten in piles by itself, but everyone decides that this is a waste of time. Given the realities, it is decided that during the transition, 10 people get the day off, even though everyone is hungry. That is just how bad Krugman's advice was.

Conclusion

As our simple story illustrates, in modern economies workers use capital goods to augment their labor as they transform nature's gifts into consumption goods. Because of the time structure of production, it is possible to temporarily boost everyone's consumption, but only at the expense of maintaining the capital goods (the boats and nets), which are thus "consumed." At some point, engineering reality sets in, and no "stimulus" policies can prevent a sharp drop in consumption.

Although the story of the sushi economy was simplistic, I hope that it illustrated essential features of a boom-bust cycle. When the islanders first implement Krugman's advice, they all feel richer. After all, they really are eating 6 rolls per day instead of 5; there is no arguing with results. And they would have no reason to suspect an unsustainable restructuring, either: after all, they are using a new outboard motor. This is analogous to the arguments about the "New Economy" during the dot-com boom, or the confidence placed in the new financial instruments used during the housing boom. During every boom, people can always come up with reasons that "this time it's different."

In the sushi economy, this initial prosperity was illusory. Although there were indeed benefits from the new technology, the bulk of the extra consumption was being financed through capital consumption, i.e., by allowing the boats and nets to deteriorate. This is analogous to Americans' consuming a massive amount of imported consumption goods during the housing boom, because they erroneously thought their rising house values would more than compensate. In other words, had Americans realized that their real-estate holdings would plummet in a few years, they would not have consumed nearly as much. They were consuming capital without realizing it, just as the islanders didn't realize that their extra sushi consumption was largely financed through neglect of their boats and nets.

Note too that this aspect of the story answers Cowen's objection: people consume more during the boom — i.e., the villagers eat more sushi per day — even while new, unsustainable investment projects are started. (In our sushi economy, the unsustainable project was looking for gasoline for the newfangled outboard motor.) Cowen is right that a sustainable lengthening of the capital structure initially requires a reduction in consumption; what happens is investors abstain and plow their savings into the new projects. But during a central-bank-induced boom, there hasn't been real savings to fund the new investments. That's why the boom is unsustainable, but it also explains why consumption increases at the same time. It's true that this is impossible in the long run, but in the short run it is possible to increase investment in new projects, and to increase consumption at the same time. What you do is neglect maintenance on critical intermediate goods, just as our islanders were able to pull off the feat for a few months. A modern economy is very complex, and it can take a few years for an unsustainable structure to become recognized as such.

Finally, our sushi economy showed why unemployment increases during the retrenchment. People don't like to work; they would rather lounge around. In order for it be worthwhile to give up leisure, the payoffs from labor have to be high enough. During the "recession" period, when the islanders had to cut way back on output from the fish, rice, and sushi-roll "sectors," there weren't 100 different tasks worth doing. In our story, we stipulated that only 90 people could be usefully integrated into the production structure, at least until the fleet of boats and supply of nets start getting restored, allowing more of the "unemployed" islanders to once again have something useful to do.

In the real world, this also happens: during the recession following the artificial boom period, resources need to get rearranged; certain projects need to be abandoned (like hunting for gasoline in the sushi economy); and critical intermediate goods (like boats and nets) need to be replenished since they were ignored during the boom. It takes time for all of the million-and-one different types of materials, tools, and equipment to be furnished in order to resume normal growth. During that transition, the contribution of the labor of some people is so low that it's not worth it to hire them (especially with minimum-wage laws and other regulations).

The elementary flaw in Krugman's objection is that he is ignoring the time structure of production. When workers get laid off in the industries that produce investment goods, they can't simply switch over to cranking out TVs and steak dinners. This is because the production of TVs and steak dinners relies on capital goods that must have already been produced. In our sushi economy, the unemployed islanders couldn't jump into sushi rolling, because there weren't yet enough fish being produced. And they couldn't jump into fish production, because there weren't enough boats and nets to make their efforts worthwhile. And finally, they couldn't jump into boat and net production, because there were already enough islanders working in that area to restore the fleet and collection of nets back to their long-run sustainable level.

People in grad school would sometimes ask me why I bothered with an "obsolete" school of thought. I didn't bother citing subjectivism, monetary theory, or even entrepreneurship, though those are all areas where the Austrian school is superior to the neoclassical mainstream. Nope, I would always say, "Their capital theory and business-cycle theory are the best I have found." Our current economic crisis — and the fact that Nobel laureates don't even understand what is happening — shows that I chose wisely.

________________________________________________________

Just a reminder, the concepts up for discussion are the physical plane versus the monetary plane, savings and capital. The physical plane is all that matters. The monetary plane exists only to assist the Superorganism in its drive toward sustainability by transmitting information through prices and lubricating the flow of the physical. Savers drive everything. If they are saving, the economy will expand (sustainably or unsustainably). If they are not saving, the economy will contract. The Superorganism's natural drive is toward economic sustainability while the $IMFS is a pedal-to-the-metal consumption binge thrill ride toward economic collapse. Savers drive the economy, the Superorganism organizes it, and the $IMFS kills it softly.

Sincerely,

FOFOA

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)